In 1882, Darwin reached his 74th year Earthworms had been published the previous October, and for the first time in decades he was not working on another book. He remained active in botanical research, however. Building on his recent studies in plant physiology, he investigated the reactive properties of roots and the effects of different chemicals on chlorophyll by examining thin slices of plant tissue under a microscope. When not experimenting, he was busy engaging with readers on Earthworms, the relationship between science and art, and the intellectual powers of women and men. He fielded repeated requests for autographs, and provided financial support for scientific colleagues or their widows facing hardship. Darwin had suffered from poor health throughout his adult life, but in February he began to feel more weak than usual. To Lawson Tait, he remarked, ‘I feel a very old man, & my course is nearly run’ (letter to Lawson Tait, 13 February 1882). His condition worsened in March. Regular walks grew difficult, and by early April, he was being carried upstairs with the aid of a special chair. The end came on 19 April. Plans were made for a burial in St Mary’s churchyard in Down, where his brother Erasmus had been interred in 1881. But some of his scientific friends quickly organised a campaign for Darwin to have greater public recognition. In the end, his body was laid to rest in the most famous of Anglican churches, Westminster Abbey.

Botanical work

Botanical observation and experiment had long been Darwin’s greatest scientific pleasure. The year opened with an exchange with one of his favourite correspondents, Fritz Müller. The men discussed the movement of leaves in response to light, and the comparative fertility of crosses between differently styled plants (letter from Fritz Müller, 1 January 1882, and letter to Fritz Müller, 4 January 1882). These were topics that Darwin had been investigating for years, but he was always keen to learn more. One line of research was new: ‘I have been working at the effects of Carbonate of Ammonia on roots,’ Darwin wrote, ‘the chief result being that with certain plants the cells of the roots, though not differing from one another at all in appearance in fresh thin slices, yet are found to differ greatly in the nature of their contents, if immersed for some hours in a weak solution of C. of Ammonia’. Darwin’s interest in root response and the effects of different chemical substances followed from his previous work on insectivorous plants and the physiology of movement. The results of this research were published in two papers, ‘Action of carbonate of ammonia on chlorophyll’ and ‘Action of carbonate of ammonia on roots’, read at the Linnean Society of London on 6 and 16 March, respectively.

In January, Darwin corresponded with George John Romanes about new varieties of sugar cane produced by grafting. In 1880, Darwin had been sent details of experiments performed in Brazil by the politician and farmer Ignacio Francisco Silveira da Motta. More documents were sent the following year from Brazilian farmers and the director of parks and gardens in Rio de Janeiro, Auguste François Marie Glaziou (see Correspondence vol. 28, letter from Arthur de Souza Corrêa, 20 October 1880, and Correspondence vol. 29, letter from Arthur de Souza Corrêa, 28 December 1881). Darwin had a long-running interest in such cases, and Romanes had made numerous attempts to produce hybrids through grafting root vegetables such as potatoes, carrots, and beets. Romanes’s experiments had been conducted to lend support to Darwin’s theory of pangenesis (see Correspondence vol. 23 and Variation 2: 357–404), but they had met with little success. He was eager to write up the results on Brazilian cane, with Darwin providing a detailed outline: ‘I had no intention to trouble you about preparing the paper,’ Darwin wrote, ‘but you seem to be quite untirable & I am glad to shirk any extra labour’ (letter to G. J. Romanes, 6 January 1882). The finished paper, ‘On new varieties of the sugar-cane produced by planting in apposition’, was read at the Linnean Society on 4 May, but not published.

Darwin carried on with botanical work in spring. He tried to obtain cobra poison, probably intending to test its effects on chlorophyll (letter to Joseph Fayrer, 30 March 1882). He received a specimen of Nitella opaca, a species of freshwater green algae, and applied more carbonate of ammonia to its roots. ‘The grains swell & then exhibit the contained particles of starch very clearly,’ he wrote to Henry Groves, the botanist who had supplied the specimen. ‘Some of the grains become confluent, occasionally sending out prolongations. But my observations are hardly trustworthy … how little we know about the life of any one plant or animal!’ (letter to Henry Groves, 3 April 1882). He wrote to an American in Kansas for seeds of Solanum rostratum, the flowers of which are asymmetric, thus facilitating cross-fertilisation. Darwin’s aim, he said, was just to ‘have the pleasure of seeing the flowers & experimentising on them’ (letter to J. E. Todd, 10 April 1882). While enthusiasm drove him, deteriorating health made it increasingly difficult to work: ‘I find stooping over the microscope affects my heart’ (letter to Henry Groves, 3 April 1882).

Earthworms and evolution

Darwin’s last book, Earthworms, had been published in October 1881. It proved to be very popular, with reviews appearing in a wide range of journals and newspapers (see Correspondence vol. 29, Appendix V). The conservative Quarterly Review, owned by Darwin’s publisher John Murray, carried an anonymous article on the book in January 1882. The reviewer’s assessment was mixed: ‘we still remain convinced of the prematureness … of what is commonly … styled the Darwinian theory of Evolution. But this difference of opinion … is no obstacle to our entertaining the highest admiration for those researches themselves’ (Quarterly Review, January 1882, p. 179). Darwin commented at length on the review to Murray. He was pleased by ‘the few first pages … which [were] highly complimentary, indeed more than complimentary.’ ‘If the Reviewer is a young man & a worker in any branch of Biology,’ Darwin continued, ‘he will assuredly sooner or later write differently about evolution’ (letter to John Murray, 21 January 1882). The author was in fact the clergyman and professor of ecclesiastical history Henry Wace. Darwin was confident that the theory of evolution would prevail, even if natural selection remained less widely accepted. ‘Literally I cannot name a single youngish worker who is not as deeply convinced of the truth of Evolution as I am, though there are many who do not believe in natural selection having done much,—but this is a relatively unimportant point. Your reviewer is in the position of the men who stuck up so long & so stoutly that the sun went round the earth’.

Particular points in Earthworms were taken up by individual readers. James Frederick Simpson, a musical composer, had provided Darwin with observations on worm behaviour, such as the rustling noise made when dragging leaves into their burrows (Correspondence vol. 29, letter from J. F. Simpson, 8 November 1881). He remarked on the ‘far reaching inferences & hypotheses’ of the book, and was inspired to continue his observations: ‘I have watched with great interest lately the building up of a “tower” casting in our little garden. Morning by morning it shows a new deposit of its viscid-“lava” on the summit, whence it rolls down the sides’ (letter from J. F. Simpson, 7 January 1882). The agricultural chemist Joseph Henry Gilbert was struck by the benefits of worms to soil composition. He asked Darwin about the nitrogen content in the castings, and whether worms might bring the element up from lower depths through burrowing. Darwin regretted that he had not studied deep sections of earth, but speculated: ‘worms devour greedily raw flesh & dead worms … And thus might locally add to amount of nitrogen … I wish that this problem had been before me when observing, as possibly I might have thrown some little light on it, which would have pleased me greatly’ (letter from J. H. Gilbert, 9 January 1882, and letter to J. H. Gilbert, 12 January 1882). In Earthworms, p. 305, Darwin had remarked on the creatures’ remarkable muscular power. This was confirmed by one of his correspondents. A clerk, George Frederick Crawte, recounted a violent contest between a worm and a frog: ‘when I first discovered them half the worm had disappeared down the frog’s throat. I watched them for a quarter of an hour and during that time the tussle was pretty severe. The worm on several occasions threw the frog on its back, and, though apparently unable to disengage itself, the annelid seemed to have rather the best of the fight’ (letter from G. F. Crawte, 11 March 1882). The battle apparently ended in a draw, with both combatants the worse for wear.

Darwin’s writing on human evolution continued to attract interest. His 1876 article ‘Biographical sketch of an infant’, based on observations of his first child, William, was republished in a collection of papers on infant development edited by the American educator Emily Talbot (Talbot ed. 1882). His letter to Talbot written the previous year (Correspondence vol. 29, letter to Emily Talbot, 19 July 1881) was also published in the Journal of Social Science, together with other materials, including extracts from the diary of Bronson Alcott, who, like Darwin, had made detailed observations of his children, one of whom became the famous writer Louisa May Alcott. The importance of Darwin’s work in inspiring future research was sounded by the American publisher, Allen Thorndike Rice: ‘This line of investigation, I am confident, will be pursued here with all the characteristic ardor and acuteness of the American intellect— indeed it is very probable that it will become a veritable craze. What I apprehend, however, is that, having become a craze, it will have the fate of all crazes: that it will be overdone, and ridiculed out of existence by the flippant witlings of the newspaper press’ (letter from A. T. Rice, 4 February 1882). Rice looked to Darwin to provide the ‘movement’ with urgently needed guidance, offering generous payment for an article in his journal, North American Review. Darwin nearly always declined such offers, and this was no exception.

Another American, Caroline Kennard, had written on 26 December 1881 (see Correspondence vol. 29) to ask Darwin whether he agreed with the commonly held view that women were intellectually inferior to men. Darwin referred her to Descent of man, where he argued that among ancestral humans and savages, males had evolved superior strength, courage, and energy, as well as higher powers of reason, invention, and imagination, as a result of their battle with other males during maturity for the possession of females; and that in civilised societies, these powers were reinforced by continued rivalry between men, and their role as providers for the family. In his letter, he conceded that there was ‘some reason to believe that aboriginally … men & women were equal’. But such equality, he insisted, required women to become ‘regular ‘’bread-winners’’’ and this would have dire consequences: ‘we may suspect that the early education of our children, not to mention the happiness of our homes, would in this case greatly suffer’ (letter to C. A. Kennard, 9 January 1882). Kennard’s reply must be read in full to be appreciated. The gist of her counter-argument was that many women were, in practice, already ‘bread winners’, as well as educators, household managers, and partners in business, though seldom recognised as such.

Which of the partners in a family is the breadwinner where the husband works a certain number of hours in the week and brings home a pittance of his earnings (the rest going for drinks & supply of pipe) to his wife; who, early & late, with no end of self sacrifice in scrimping for her loved ones, toils to make each penny tell for the best economy and besides, to these pennies she may add by labor outside or taken in? … The family must be righteously maintained … Let the ‘environment’ of women be similar to that of men and with his opportunities, before she be fairly judged, intellectually his inferior, please (letter from C. A. Kennard, 28 January 1882).

Automata and vivisection

Darwin had a less heated discussion with the painter John Collier on the topic of science and art. He had sat for Collier in 1881 for a portrait commissioned by the Linnean Society. Collier sent Darwin a copy of his Primer of art (Collier 1882), which seemed to follow Darwin’s views on the aesthetic sense of animals, and its role in the selection of mates. ‘Will not your brother-artists scorn you for showing yourself so good an evolutionist’, Darwin joked. ‘Perhaps they will say that allowance must be made for him, as he has allied himself to so dreadful a man, as Huxley’ (letter to John Collier, 16 February 1882). Collier had married Thomas Henry Huxley’s daughter Marian. He returned the joke: ‘I am in hopes that my brother artists will not read the work in question if they did my character amongst them would be gone for ever and I should be classed (most unjustly) as a scientific person’. The two men also agreed on the deficiencies of Huxley’s argument that animals were conscious automata, and that human consciousness might be analogous to the smoke coming out of a steam engine, of no practical use. ‘There must be something wrong in a theory which nobody really believes in with regard to himself except in some strained & unnatural sense— Would my actions be the same without my consciousness?’ (letter from John Collier, 22 February 1882; T. H. Huxley 1881, pp. 199–245).

Huxley used arguments about automatism in debates over vivisection, attempting to undermine claims of animal suffering. Darwin had taken a strong interest in the vivisection debate in 1875, and had even testified before a Royal Commission that experiments performed without regard for animal suffering were reprehensible (see Correspondence vol. 23, Appendix VI). But he also strongly supported experimental physiology as a discipline. In February he contributed a large sum (£100) to the ‘Science Defence Association’, an organisation made up largely of medical professionals interested in promoting physiological research. ‘I feel a deep interest in the success of the proposed Association,’ he wrote to William Jenner, ‘for I am convinced that the benefits to mankind to be derived from basing the practice of medicine on a solid scientific foundation cannot be overestimated’ (letter to William Jenner, 20 March [1882]; see also letter from T. L Brunton, 12 February 1882, and letter to T. L. Brunton, 14 February 1882).

Father and grandfather

Darwin continued to delight in his children’s accomplishments. In a letter to Anthony Rich, he shared several of his sons’ achievements. Leonard had been appointed to observe the transit of Venus on an expedition to Queensland, Australia. George’s recent work had been highly praised by his scientific peers. A lecture by Robert Stawell Ball that was printed in Nature declared George ‘the discoverer of tidal evolution’ (Nature, 24 November 1881, p. 81). Darwin boasted to Rich: ‘George’s work about the viscous state of the earth & tides & the moon has lately been attracting much attention, & all the great judges think highly of the work … I believe that George will some day be a great scientific swell’. Darwin also mentioned George’s heavy workload as an examiner for the mathematical tripos at Cambridge, and his plans to take a long trip to Jamaica ‘for complete rest’ (letter to Anthony Rich, 4 February 1882). Horace had settled in Cambridge with his wife, Ida, and continued to build up his scientific instrument company, but his biggest news was the birth of his first child (Erasmus Darwin) on 7 December 1881. Finally, Darwin had a second grandchild to spoil and gloat over.

The final illness

Although Darwin had been plagued by illness for much of his adult life, the last decade or so had seen relative improvement. His reply to a correspondent about the effects of tobacco and alcohol on intellectual work reveals his daily regimen: ‘I drink 1 glass of wine daily and believe I should be better without any, though all Doctors urge me to drink some or more wine as I suffer much from giddiness. I have taken snuff all my life and regret that I ever acquired the habit, which I have often tried to leave off and have succeeded for a time. I feel sure that it is a great stimulus and aid in my work. I also daily smoke 2 little paper cigarettes of Turkish tobacco. This is not a stimulus, but rests me after my work, or after I have been compelled to talk, which tires me more than anything else. I am now 73 years old’ (letter to A. A. Reade, 13 February 1882). Over the month of February, Darwin started to feel more poorly than usual. An entry in his diary for 7 March records: ‘I have been for some time unwell’ (Darwin pocket diary, 1882, Down House MS). On a visit to Down in early March, Henrietta learned that her father had been experiencing some pain in the heart after his regular walks. Several days later he had a ‘sharp fit’ while on the Sandwalk, and was no longer able to take his daily strolls (Henrietta Emma Litchfield, ‘Charles Darwin’s death’, DAR 262.23: 2, p. 2). His physician for some years was the prominent London practitioner Andrew Clark. On 9 March, Darwin wrote in his diary, ‘Dr. Clark came to see me on account of my heart’. He was prescribed morphia pills, as well as a ‘Simple Antispasmodic’ and a ‘Glycerin Pepsin mixture’ (letters to W. W. Baxter, 11 March 1882 and 18 March [1882]). Detailed instructions followed on diet, reduced activity, and medications. The treatments were not for Darwin’s usual stomach troubles and nausea. The anti-spasmotic (possibly amyl nitrate) and morphine lozenges were for severe chest pain (see Colp 2008, pp. 116–20). ‘On rising’, Clark wrote, ‘sponge with tepid or warm water dry quickly and use as little exertion as possible … Especially avoid lifting straining going upstairs when it can be avoided hurrying or doing anything which will bring on the chest pain. Short of this walk about gently’ (letter from Andrew Clark, 17 March 1882).

Darwin’s family and close friends grew worried. Letters were sent to George, who was soon to return from Jamaica. ‘Mother keeps very well’, wrote Henrietta, ‘tho' she is depressed for Father. I am afraid he is a good deal depressed about himself’ (letter from H. E. Litchfield to G. H. Darwin, 17 March 1882 (DAR 245: 319)) Emma wrote ten days later: ‘You will find F. rather feeble & unwell. We had Dr Clark to see him about 3 weeks ago, as he had been a good deal plagued with dull aching in the chest’ (Emma Darwin to G. H. Darwin, [c. 28 March 1882] (DAR 210.3: 45)). Huxley urged Darwin to consult another physician. ‘Ever since I met Frank at the Linnean,’ he wrote, ‘I have been greatly exercised in my mind about you … What I want you to do is to get one of the cleverer sort of young London Doctors such as Brunton or Pye Smith to put himself in communication with Clark & then come & see you regularly … you really ought to have somebody in whom dependence can be placed to look after your machinery (I daren’t say automaton) critically’ (letter from T. H. Huxley, 25 March 1882). Darwin was very grateful for the advice, and returned the joke about automata: ‘Your most kind letter has been a real cordial to me.— I have felt better today than for 3 weeks & have had as yet no pain.— Your plan seems an excellent one … Dr Clark’s kindness is unbounded to me, but he is too busy to come here … I wish to God there were more automata in the world like you’ (letter to T. H. Huxley, 27 March 1882).

Darwin did not improve. He continued to make brief entries in his diary: ‘very tired’, ‘only traces of pain’, ‘slight attack’ (Darwin pocket diary, 1882, 6, 7, 10 April 1882). Some days he was able to walk in the garden, or spend time in the drawing-room. As he grew weaker, however, he could no longer mount the stairs to his bedroom: ‘He certainly finds being carried upstairs (in a carrying chair Jackson fetched yesterday) a benefit & he escaped pain entirely yesterday’ (letter from Emma Darwin to G. H. Darwin, 6 April 1882 (DAR 210.3: 46)). Despite his declining condition, Darwin continued to answer scientific correspondents, and fielded requests for money and autographs. He wrote to Adolf Ernst about an earthworm from Venezuela (letter to Adolf Ernst, 3 April 1882). He sent a cheque for a memorial to the late George Rolleston (letter to H. N. Moseley, 7 April 1882). He wrote twice to an American autograph collector and his two sisters, who requested separate notes so that each Darwin signature could be framed and hung in their respective bedrooms. When his initial reply in February went missing, the appeal was renewed with more urgency: ‘Oh, Mr Darwin, I beseech of you in behalf of my dear sisters & everything that is sacred to me, as well as my own great desires, grant us this our modest request!’ (letter from J. L. Ambrose, 3 April 1882). Darwin immediately sent another set of cards, each signed ‘your well-wisher’ (letter to J. L. Ambrose, 15 April 1882). The last letter that he wrote was to the vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge, enclosing a subscription for the portrait of William Cavendish, the duke of Devonshire and chancellor of the university (letter to James Porter, 18 April 1882).

The final attack came on the night of 18 April, and carried him off the next day. Henrietta immediately wrote to George, who had visited Down on 11 April (Emma Darwin’s diary (DAR 242)). ‘Father was taken very ill last night with great suffering … Mother said he was longing to die & he sent us all an affectionate message. He told her he was not the least afraid to die. Mother is very calm but she has cried a little’ (letter from H. E. Litchfield to G. H. Darwin, [19 April 1882] (DAR 245: 320)). It was left to Emma to convey the sorrowful news to his closest friends. She wrote to Joseph Dalton Hooker the day after Darwin’s death. ‘Our hopes proved fallacious & on Tuesday night an attack of pain came on accompanied with fainting— It was a terrible time till all was over (about 15 hrs) but the faintness & sickness & exhaustion were worse than the pain, which I hope were never very violent’ (letter from Emma Darwin to J. D. Hooker, [20 April 1882]).

In the coming weeks, Emma found great comfort in her family. ‘It is always easier to write than to speak,’ she wrote to Leonard, ‘& so though I shall see you so soon I will tell you that the entire love & veneration of all you dear sons for your father is one of my chief blessings & binds us together more than ever. When you arrived on Thursday in such deep grief I felt you were doing me good & enabling me to cry, & words were not wanting to tell me how you felt for me— Hope [Wedgwood] expresses a feeling that I should not be pitied after what I have possessed & have been able to be to him’ (letter from Emma Darwin to Leonard Darwin, [21? April 1882] (DAR 239.23: 1.13)). She also found relief in some of Darwin’s letters, remarking to William: ‘I have been reading over his old letters. I have not many we were so seldom apart, & never I think for the last 15 or 20 years, & it is a consolation to me to think that the last 10 or 12 years were the happiest (owing to the former suffering state of his health which appears in every letter) as I am sure they were the most overflowing in tenderness’ (letter from Emma Darwin to W. E. Darwin, 10 May 1882 (DAR 219.1: 150)).

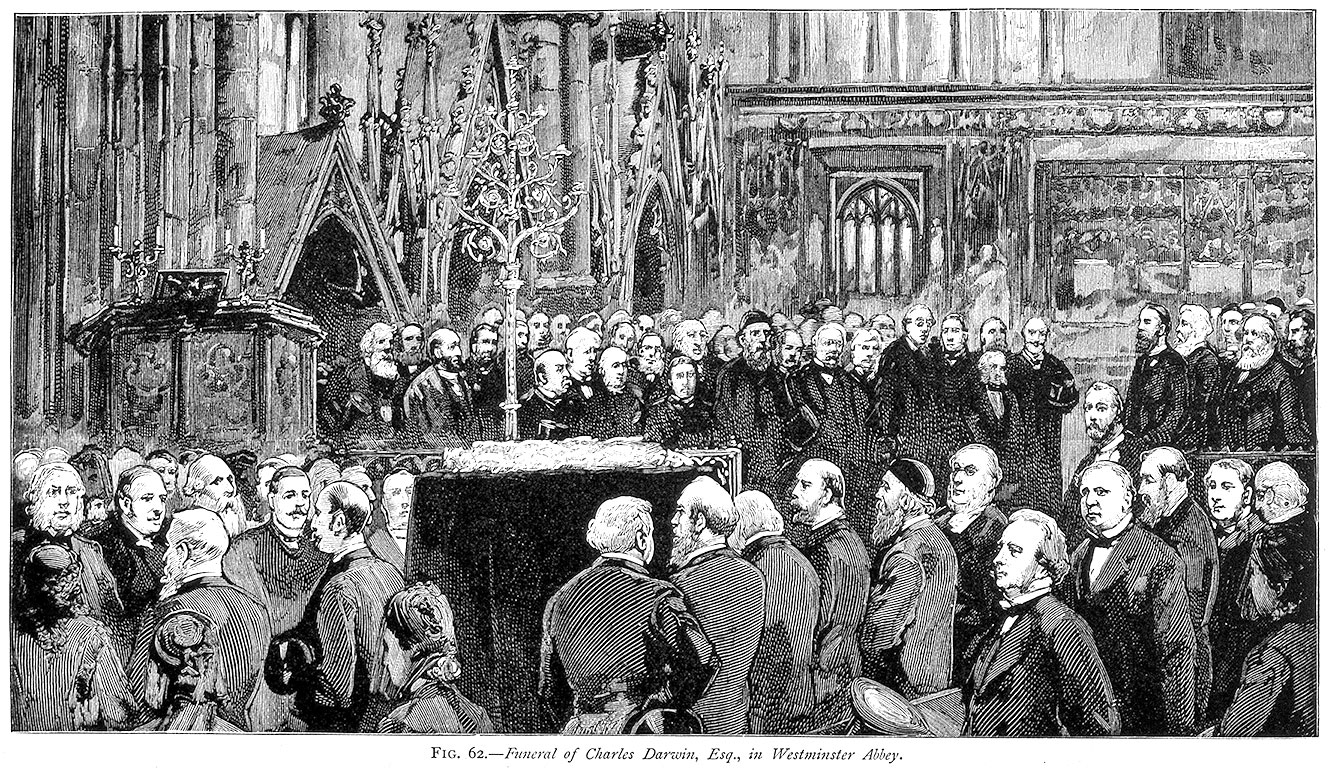

Letters of condolence arrived from Darwin’s scientific friends, correspondents, and admirers. One of the most touching was from John Lubbock, whose interest in natural history at an early age was encouraged by Darwin. He wrote to Francis: ‘I say nothing about the loss to Science for all feeling of that kind is swallowed up by my sorrow that I shall never see him again. For thirty years & more your father has been one of my kindest & best friends & I cannot say how I shall miss him. Out of his immediate family no one will mourn his loss or cherish his memory more than I shall. I have just come from the Linnean when we adjourned as a small tribute of respect’ (letter from John Lubbock to Francis Darwin, 20 April 1882 (DAR 215: 10n)). Lubbock was among the group of friends who sought public recognition for Darwin in the form of a ceremony and burial in Westminster Abbey. The event was attended by many dignitaries, leading clergymen, politicians, and presidents of scientific societies, as well as immediate and extended family and several of the Down House servants. Details of the funeral can be found in Appendix IV. Lengthy obituaries flooded the British and international press. Personal reminiscences from colleagues and friends were published. More polemical tributes also quickly appeared. The American satirical magazine Puck carried a full-page colour illustration of Darwin as the ‘sun of the nineteenth century’, piercing the gloomy clouds of priest-craft and bibliolatry.

Supplement

While Darwin’s death brings 1882 to an early close, this volume contains a supplement of nearly 400 letters. Many of these were discovered since the publication of volume 24, which contained the most recent supplement, while others were given broad date ranges, often because they are incomplete. The supplement covers nearly the whole period of Darwin’s career, offering glimpses of his activity at different stages of life. There are a few letters from the Beagle voyage, including detailed instructions for inland travel from Buenos Aires, noting where to catch fish, where to find lodging, and what types of vegetation and potentially dangerous animal life to expect, such as jaguars, deadly snakes, centipedes, and spiders. The instructions were from Charles Lawrence Hughes, a fellow pupil of Darwin’s at Shrewsbury School who had been a clerk in Buenos Aires but was forced to return to England because of ill health. ‘I would strongly recommend you to go some distance into the country to some Estancia,’ wrote Hughes, ‘as the scenery &c. will amply repay your trouble’ (letter from C. L. Hughes, 2 November 1832). Darwin made the journey on horseback up the river Uruguay to Rio Negro in November 1833. Darwin also received a detailed map that he used to travel inland from Santiago in 1834, making observations of geological uplift (letter from Thomas Sutcliffe, [28 August – 5 September 1834]). His investigations were assisted by notes and a diagram of an old sea wall in Valparaiso, where he had witnessed an earthquake in 1835 (letter from R. E. Alison, [March–July 1835]).

Darwin’s return from the voyage was eagerly awaited by his family, including his cousin Emma Wedgwood. In long letters to her sister Fanny and cousin Louisa Holland, she mentions his warm reception on arrival: ‘Charles is as well as possible & in gayer spirits than I ever remember him’. ‘[He] talked away most pleasantly all the time we plied him with questions without any mercy’ (letter from Emma Wedgwood to F. E. E. Wedgwood, [28 October 1836], letter from Emma Wedgwood and Louisa Holland to F. E. E. Wedgwood, [21 and 24 November 1836]). Another batch of letters provides glimpses of Darwin’s scientific life in the 1840s: his duties as secretary of the Geological Society, his work on geology, coral reefs, and barnacles. We see how he initiated correspondence to more established figures, seeking information or specimens. Hard at work on cirripedes, he wrote to the geologist Wilhelm Dunker to request fossil specimens from Germany: ‘As my name will probably be unknown to you, I may mention, as a proof that I am devoted to Natural History, that I went as Naturalist on the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the World & collected in all branches of Nat. History. I trust to your kindness to forgive my intruding myself on you’ (letter to Wilhelm Dunker, 3 March [1850]).

In the mid-1850s, Darwin was slowly preparing his ‘big book’ on species, trying to gather more varieties of pigeons and other domestic animals for study. He wrote to the gentleman expert Edward Harcourt, a specialist on birds and a pigeon breeder: ‘Skins are on their road to me sent by Mr. Murray from Persia, & I hope to get all the breeds from India & China. Any assistance of this nature would be invaluable; but I know it is much too troublesome to expect you yourself to skin birds for me, & I fear there is little chance of your being able to find anyone who could skin; but if this were possible, & you could hear of any breeds of Pigeon, believed to have been long kept in Ægypt, I would gratefully, with your permission, repay you for their purchase & skinning. … Any observations on any of the domestic animals, as Ducks, Poultry, Rabbits (the skeletons of which I am collecting with great pains)… would be very interesting to me’ (letter to E. W. V. Harcourt, 24 June [1856]). In a follow-up letter, Darwin hinted at the central role that domestic pigeon breeds and their common descent from the rock dove would play in the first chapter of Origin: ‘I have found Blue birds with the foregoing characters, in all the Breeds, & it is one of my arguments, that all [pigeons] have descended from the Rock’ (letter to E. W. V. Harcourt, 13 December [1857]).

In May 1857, Darwin wrote to the secretary of the Royal Society, William Sharpey, with recommendations for annual medals. He strongly supported Charles Lyell for the Copley, the Royal Society’s highest award, revealing the degree to which he valued the work of the eminent geologist. ‘It is my deliberate conviction that the future Historian of the Natural Sciences, will rank Lyell’s labours as more influential in the advancement of Science, than those of any other living man, let him be who he may; & I do not think I am biassed by my old friendship for the man … The way I try to judge of a man’s merit is to imagine what would have been the state of the Science if he had not lived; & under this point of view I think no man ranks in the same class with Lyell’ (letter to William Sharpey, 22 May [1857]).

There are a few letters shortly after the publication of Origin. Huxley had written a number of glowing reviews of the book, including a high-profile article in The Times. Darwin sent him a copy of the second edition, adding: ‘You have been beyond all or nearly all the warmest & most important supporter … I am beginning to think of, & arrange my fuller work; & the subject is like an enchanted circle; I cannot tell how or where to begin’ (letter to T. H. Huxley, 21 [January 1860]). Darwin’s former mentor at University of Cambridge, John Stevens Henslow, was not a transmutationist, but the men remained on the best of terms. Darwin invited him to visit Down for lively discussion: ‘I shall be particularly glad to hear any of your objections to my views, when we meet’ (letter to J. S. Henslow, 29 January [1860]). Origin would bring Darwin much more into the public eye. A Polish landowner and collector heaped praise upon him and requested an autograph: ‘I … have been filled with esteem and admiration for your great genius, which has glittered and gleamed like a blessed light in today’s science … I would preserve this script like a holy relic among my valuables, as a keepsake for the Fatherland and its descendants, as a sign, of how deeply and highly the Poles know how to value great minds’ (letter from Aleksander Jelski, [1860–82]).

In 1863, the final blow was dealt to Darwin’s theory on the origins of the ‘parallel roads’ of Glen Roy. In one of his earliest geological publications, he had argued that the terraces running along the sides of a glen in Scotland were the remains of ancient seashores left behind by gradual elevation of the land (‘Parallel roads of Glen Roy’). An alternative theory of ice dams causing glacial lakes was presented by Thomas Francis Jamieson in a paper to the Geological Society. Darwin was a referee for the paper and he wrote offering full support and praise for its author: ‘I heartily congratulate you on having solved a problem which has puzzled so many and which now throws so much light on the grand old glacial period. As for myself, you let me down so easily that, by Heavens, it is as pleasant as being thrown down on a soft hay-cock on a fine summer’s day. There are other men who would have had no satisfaction without hurling us all on the hard ground and then trampling on us. You cannot do the trampling at all well—you cannot even give a single kick to a fallen enemy!’ (letter to T. F. Jamieson, 24 January [1863]).

From 1863 to 1865, Darwin suffered the most extended period of poor health in his life. ‘The doctors still maintain that I shall get well,’ he wrote to Alfred Russel Wallace, ‘but it will be months before I am able to work’ (letter to A. R. Wallace, [c. 10 April 1864]). To the physician Henry Holland, he remarked. ‘I shall never reach my former modicum of strength: I am, however, able to do a little work in Natural History every day’ (letter to Henry Holland, 6 November [1864]). Writing to the clergyman and naturalist Charles Kingsley, he was more gloomy: ‘One of the greatest losses which I have suffered from my continued ill-health has been my seclusion from society & not becoming acquainted with some few men whom I should have liked to have known’ (letter to Charles Kingsley, 2 June [1865]).

In the years following Origin, a number of Darwin’s friends, Huxley, John Lubbock, and Charles Lyell, each addressed the question of human descent. Darwin had been particularly disappointed with Lyell’s Antiquity of man, which failed to extend the theory of evolution to humans. In letters, however, Lyell had been a strong advocate of common descent. In 1867, Lyell expressed his enthusiasm for Darwin’s decision to take up the subject. ‘I shall be very curious to read what you will say on Man & his Races’, Lyell wrote. ‘It was not a theme to be dismissed by you in a chapter of your present work [Variation]. You must have so much to say & gainsay. … I am content to declare, that any one who refuses to grant that Man must be included in the theory of Variation & Natural Selection, must give up that theory for the whole of the organic world (letter from Charles Lyell, 16 July 1867). In the same year, Darwin made a rare declaration on the origins of life to the chemist George Warington, who was keen to reconcile science with religion.

It seems to me perfectly clear that my views on the Origin of Species do not bear in any way on the question whether some one organic being was originally created by God, or appeared spontaneously through the action of natural laws. But having said this, I must add that judging from the progress of physical & chemical science I expect … that at some far distant day life will be shewn to be one the several correlated forces & that it is necessarily bound up with other existing laws. But … this belief, as it appears to me, would not interfere with that instinctive feeling which makes us refuse to admit that the Universe is the result of chance.

Darwin added that religious belief was, in his view, a private matter. ‘It is not at all likely that you wd wish to quote my opinion on the theological bearing of the change of species, but I must request you not to do so, as such opinions in my judgment ought to remain each man’s private property’ (letter to George Warington, 11 October [1867]).

Respecting the privacy of religious belief, especially when views bordered on heterodoxy, often led to the suppression of material from printed editions of correspondence. Portions of a long letter from Lyell to Darwin containing his views on prayer and the afterlife were removed from the published version of Lyell’s Life, letters and journals by Lyell’s sister-in-law Katherine (see K. M. Lyell ed. 1881, 2: 445–6). A complete draft and contemporary copy have only recently been discovered. Writing just six months before his death, Lyell was remarkably frank to his old friend:

I have been lying awake last night thinking of the many conversations I have had with the dear wife I have lost, and of the late Mr. [Nassau] Seniors saying that as he was not conscious of having existed throughout an eternity of the past, how could he expect an eternity of the future. If according to this view, death means annihilation, may we not give up all discussion about prayer, for would there be anything worth praying for, there being no future life.

I can easily conceive an eternal omnipresent and omniscient mind coexistent with Matter, and Force, and like them indestructible, but … all this carries us into the unknowable and incomprehensible, and I must not make you my father confessor. (Letter from Charles Lyell, 1 September 1874.)

Darwin’s fame continued to grow, and he attracted many admirers in German-speaking countries. In 1869, his birthday was celebrated by an article in the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse. The Austrian librarian Ferdinand Maria Malven informed Darwin that his name was ‘here and everywhere in Germany as worshiped as that of our ever-lamented immortal Humboldt’ (Correspondence vol. 17, letter from F. M. Malven, 12 February [1869]). An extract from Darwin’s reply to Malven was published in a later issue of the newspaper: ‘Since my boyhood I have honoured Humboldt’s name, and it was his works that awoke in me the desire to see and investigate tropical countries; so I consider it a great honour that my name should be connected with that of this leader of science, but I am not so weak as to assume that my name could ever be placed in the same class with his’ (letter to F. M. Malven, [after 12 February 1869]). Accompanying this extract was the comment that it gave the lie to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s famous dictum, ‘Nur die Lumpe sind bescheiden’ (Only nobodies are modest). Darwin gradually built up a strong network of correspondents among German naturalists, some of whom drew substantially on his theory. In 1869, Hermann Müller (brother to Fritz) sent Darwin his recent work on the co-adaptive structures of insects and flowers (‘Die Anwendung der Darwin’schen Lehre auf Blumen und blumen-besuchende Insekten’ (The application of Darwinian theory to flowers and flower-visiting insects; H. Müller 1869)). Darwin was full of admiration and suggested further lines of research: ‘The importance of butterflies, who do not consume pollen, for flowers never occurred to me, and your considerations explain the enormous development of nocturnal species. It seems very odd to me, that there should be no nocturnal nectar-drinking Diptera or Hymenoptera. Has anyone investigated the stomach contents of bats?’ (letter to Hermann Müller, 14 March 1870).

One of Darwin’s other great loves, dogs, was indulged by George Cupples, a writer and experienced deerhound breeder. He offered Darwin a puppy of the large hunting breed. Darwin could not refuse, and christened the dog ‘Bran’. ‘I am delighted to hear about the Dog; but as I said before you have been too generous to make me such a present. I do not feel worthy of it, except so far that when I know a dog, I love it with all my heart & soul.— … I should be very grateful for a few instructions about food & name of Father or near relatives that we may Christian him … Any hints, if necessary, about teaching him to be quiet & not attack men or animals wd. be advisable. I can assure you, we will all make much of him’ (letter to George Cupples, 20 September [1870]).

Despite Darwin’s insistence that natural selection was less important than the general acceptance of evolution, he continued to engage with critics of his work, and to defend particular aspects of his theory. He discussed the gradual development of pedicellariae (small pincer-like appendages in echinoderms) with the Swiss zoologist Alexander Agassiz: ‘Over & over again I have come across some structure, & thought that here was an instance in which I shd. utterly fail to find any intermediate or graduated structure; but almost always by keeping a look out I have found more or less plain traces of the lines through which development has proceeded by short & easy & serviceable steps’ (letter to Alexander Agassiz, 28 August [1871]; see also Correspondence vol. 19, letter from Alexander Agassiz, [before 1 June 1871]). Agassiz’s view that the pedicellariae were modified spines, and were thus of benefit to the animals throughout their development, was used by Darwin against his most aggressive critic, St George Jackson Mivart, who claimed that the organs were useless unless fully formed, and so could not have evolved by natural selection (see Origin 6th ed., pp. 191–2).

Darwin was often asked to support social and political causes. He expressed his willingness to contribute to a fund to assist Sophia Jex-Blake’s legal expenses, incurred as a result of her struggle to obtain a medical degree at Edinburgh. ‘I have the honour to acknowledge, on the part of Mrs Darwin & myself, the request that we should agree to our names being added to the General Committee for securing medical education to women. I shall be very glad to have my name put down, or that of Mrs Darwin but I should not like both our names to appear’ (letter to Louisa Stevenson, 8 April 1871). It was Darwin’s name that was entered on the list. Blake eventually obtained an MD from Dublin and went on to practise medicine in Edinburgh.

Women’s education was often linked to other causes by reformers. Some feminists supported what they believed to be a progressive form of eugenics, with improved conditions for women allowing them to exercise more power over the choice of mates, and so be better able to shape the future of the nation and the human race. Darwin’s views on eugenics, a term coined by his cousin Francis Galton, were mixed, partly owing to the complexity of his views on heredity. His belief in human improvement was tested by Henry Keylock Rusden, an Australian public servant and writer who supported women’s emancipation, but also eugenic measures to eliminate the unfit. Rushden sent Darwin several pamphlets that advocated a ban on reproduction for lunatics, and the permanent incarceration of convicted criminals, even their use in medical experiments. Darwin was partially in agreement: ‘I have long thought that habitual criminals ought to be confined for life, but did not lay stress enough until reading your essays on the advantages of thus extinguishing the breed. Lunacy seems to me a much more difficult point from its graduated nature: some time ago my son, Mr G. Darwin, advocated that lunacy should at least be a valid ground for divorce’ (letter to H. K. Rusden, [before 27 March 1875]). In Descent of man, p. 103, Darwin had noted that humans were the only species that showed sympathy for all living creatures, including the weak, ‘the imbecile, the maimed, and other useless members of society’. He regarded this as the highest measure of ‘humanity’, a result of ‘sympathies grown more tender and widely diffused’. But he also cited Galton and others for the observation that the poor and degraded seemed to reproduce earlier and thus in greater numbers than the wise and prudent (Descent, pp. 173–4). Progress, Darwin warned, was not preordained.

It was with great relief that Darwin finished his work on human evolution, and was able to spend the remaining years of his life on less controversial subjects. Letters from the last years of Darwin’s life show his increasing attachment to Francis, as father and son worked together on botanical experiments. Francis went to Germany in the summer of 1878 for more experience in physiological botany. Many letters were exchanged in the period when he was away. Darwin showed how much he missed having his son to work with, writing almost daily to share his results. ‘I have made yesterday & day before some observations which have surprised me greatly. The tendrils of Bignonia capreolata (as described in my book) are wonderfully apheliotropic, & the tips of quite young tendrils will crawl like roots into any little dark crevices. So I thought if I painted the tips black, perhaps the whole tendril wd be paralysed. But by Jove exactly the reverse has occurred … Having no one to talk to, I scribble this to you’ (letter to Francis Darwin, [1 August 1878]).

The last years also saw Darwin return to work on earthworms, reconnecting with correspondents who had undertaken observations years earlier. In 1871, he had asked Henry Johnson to observe the thickness of mould covering the Roman remains at Wroxeter (see Correspondence vol. 19, letter to Henry Johnson, 23 December 1871, and Earthworms, pp. 221–8). Darwin resumed contact in 1878. On receiving Darwin’s letter, Johnson’s daughter, who assisted him in observations, described her father’s glee: ‘How much more lasting is the friendship between two men than two women! My father’s very warm feeling for you is not lessened by absence & he gloats over yr. books & any word of you he hears— When yr. letter came I saw such a glow of pleasure on his dear old face & with as much joy as if announcing a legacy … he said “Darwin is still at wormbs”’ (letter from Mary Johnson, [after 22 July 1878]).

Edition complete

With volume 30, the Correspondence of Charles Darwin is now complete. In the future, when new letters or missing parts of letters are found, these can be added to this digital version of the edition (darwinproject.ac.uk). The entire corpus will also be available through the nineteenth-century scientific correspondence website, epsilon.ac.uk, where it may be explored together with the letters of Darwin’s contemporaries. Both sites will be maintained by Cambridge University Library. This project was begun in 1974, a time when other Darwin manuscripts, especially the early notebooks on species, diaries, and marginalia, were also being carefully transcribed and published. The principles of meticulous textual scholarship are laid out in a preface to the first volume of the series (Correspondence vol. 1, pp. xxv–xxix). Also briefly mentioned is the decision to publish both sides of the correspondence. At the time, this was unusual, and it is still not standard practice in editions of letters. In retrospect, however, this was perhaps the most important editorial decision that was made, for it completely transformed the edition into a series of exchanges, rather than a one-sided affair. In the Victorian period, formal participation in science was highly restricted. Institutions of higher education, membership in learned societies, and positions of scientific employment were open to very few. Correspondence was by no means egalitarian, but it was a far more inclusive space for participation. Darwin gained enormously from this, expanding his network to include men and women from diverse classes, backgrounds, beliefs, and occupations. His letters show that the same interest, respect, and enthusiasm were shown to any correspondent who engaged seriously with his work, offered some careful observation, a new specimen, a comment, or a criticism. Through Darwin’s Correspondence, thousands of other lives, diverse perspectives, and divergent points of view have found a place. After Darwin’s death, one of his correspondents wrote a letter of condolence to the family. She had once ‘daringly addressed’ him on the subject of ‘how far heredity is limited by sex’, and the constraints that women faced in the pursuit of science (Correspondence vol. 23, letter from Charlotte Papé, 16 July 1875). She now addressed Francis, who could best appreciate the botanical tribute she made to his father: ‘I trust you, who once, years ago, when I was living in England, were kind enough to give a detailed reply to a question daringly addressed to your great father, will not now despise, among the mourning voices of the civilised world, the sorrowful utterance of an insignificant and unknown woman, but let it be like a little flower laid on the grave of him for whom nothing was too great and nothing too small’ (letter from Charlotte Papé to Francis Darwin, 21 April 1882, DAR 215: 7k).